Inside the Met

What Panorama Exposed

On 1 October, BBC Panorama aired a devastating investigation into the Metropolitan Police. For seven months, an undercover reporter worked inside Charing Cross police station in central London, capturing on camera what many survivors, campaigners, and community advocates have long suspected: misogyny, racism, and abuse of power are not relics of the past - they remain deeply embedded in parts of Britain’s largest police force.

The footage shows officers laughing about using force against detainees, dismissing rape allegations, and speaking with open contempt about Muslims and immigrants. Some of the language is so degrading that it is difficult to repeat. Officers described migrants as “scum,” joked about sexual assault, and suggested that women making allegations of rape were not to be believed.

For Londoners - and for survivors of sexual violence in particular - the Panorama documentary is another body blow to trust in the police.

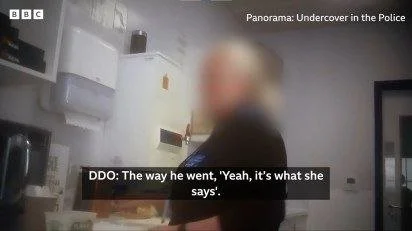

“That’s what she says”

One of the most disturbing scenes captured Sergeant Joe McIlvenny, a custody sergeant with nearly two decades of service, dismissing the account of a pregnant woman who had alleged rape and domestic violence. When a colleague raised concerns about releasing the accused on bail, noting that the man had reportedly kicked the woman in the stomach, McIlvenny replied: “That’s what she says.”

For survivors, those words are chillingly familiar. They echo a wider culture in which victims’ testimonies are too often minimised, doubted, or disbelieved. The consequences of that disbelief can be devastating. Custody sergeants make decisions about bail - decisions that affect immediate safety. When those decisions are shaped by misogyny or cynicism, women’s lives are put at risk.

Sue Fish, former Chief Constable of Nottinghamshire Police, described McIlvenny’s comments as “terrifying.” She explained why: “As a woman as well as a former police officer, individuals like him have the power to make these sorts of decisions about my safety or other women’s safety - and that is terrifying.”

Violence and impunity

The undercover footage also reveals officers boasting about unlawful violence. One constable described how a colleague, nicknamed “Stampy,” brought his boot down twice on a restrained man’s leg. Another officer talked casually about snapping tendons when taking fingerprints by force.

This is not gallows humour. These are admissions of excessive force, laughed over in pubs, traded as war stories, and cushioned by a culture where colleagues look the other way. Panorama captured officers reassuring one another that fabricated statements could cover tracks if needed. The message was clear: the system protects its own.

When violence becomes entertainment, and accountability becomes optional, the trust that underpins policing by consent erodes completely.

Racism, Islamophobia, and dehumanisation

Racism was evident in the undercover recordings with grim consistency. Officers referred to migrants and Muslims as “scum.” One constable declared that those who had overstayed their visas should be “given a bullet to the head.” Others derided entire communities as a “problem” or an “invasion.”

This language was not whispered in shame. It was expressed openly, over drinks with colleagues, shared as jokes and banter. It reflects not isolated prejudice but a worldview in which entire groups are dehumanised - an outlook that cannot be separated from how policing decisions are made on the streets, in custody suites, and in courtrooms.

Masks on, masks off

One of the most telling observations from the Panorama footage came from an officer who explained: “Someone new joins, boom, mask on. You’ve got to figure them out.”

What this reveals is not simply prejudice but performance. Officers knew that openly racist, misogynistic, or abusive remarks could get them into trouble. So they wore masks around outsiders - only removing them once trust was established.

The problem, then, is not a few “bad apples” who accidentally reveal their prejudices. It is a culture where those prejudices are normalised, where the “real you” emerges when guards are down, and where silence from colleagues protects the group.

Responses and apologies

In the wake of Panorama, London Mayor Sadiq Khan said he was “disgusted and appalled” by the behaviour. The Home Secretary called the footage “disturbing and sickening.” Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley apologised, saying the actions were “disgraceful” and “totally unacceptable.”

The Met has suspended eight officers and one staff member, and removed two more from front-line duties. Rowley also announced that the entire Charing Cross custody team had been dismantled. He pointed out that since 2022, over 1,400 officers and staff have left or been dismissed for failing to meet standards.

These steps sound decisive. Yet for survivors and communities who have lived with repeated scandals, apologies ring hollow. As Mina Smallman, whose daughters were murdered and then mocked by Met officers sharing crime scene photos, told Newsnight: “When people are comfortable and their guard is down, we get to see what they’re really like.”

The cost of disbelief

The Panorama footage matters because it shows what happens behind closed doors - when the cameras are off and survivors cannot hear what is being said about them.

When a rape allegation is dismissed with a shrug, that disbelief is not abstract. It determines whether suspects are charged, whether victims are protected, and whether survivors feel safe enough to report again.

The Casey Review, published after the murder of Sarah Everard by a serving officer, concluded that the Met was institutionally racist, misogynistic, and homophobic. Panorama suggests that, despite leadership promises, those cultural failings have not been eradicated - they have simply gone underground.

First-hand perspectives

For those of us who have sat on the Met’s Victim Voice Forum or joined Independent Advisory Groups on VAWG (violence against women and girls), the revelations land heavily.

We have seen both sides: the committed officers working tirelessly to protect survivors, and the slow but genuine progress in areas of policy, safeguarding, and survivor engagement. Yet we have also seen, time and again, how deep the resistance runs, how fragile trust remains, and how quickly one case, one headline, one investigation can unravel public confidence.

It is heartbreaking. It is exhausting. And it is why survivors and communities continue to demand more than apologies and statements of intent.

What real change requires

Change cannot mean waiting for another scandal to trigger another round of suspensions. It cannot mean relying on whistleblowers or undercover reporters to expose what leadership failed to see - or chose not to see.

Real change must mean:

Relentless accountability: officers who engage in racist, misogynistic, or violent behaviour should not be quietly moved or shielded; they should be dismissed.

Transparency: the public must see not just apologies but evidence of reform - clear data, independent scrutiny, and survivor-led oversight.

Cultural overhaul: misogyny and racism must be treated as corruption, not as “banter.” Training alone is not enough.

Listening to survivors: trust cannot be rebuilt without centring those who have been most harmed. Survivors’ voices should shape policing priorities, standards, and accountability.

A turning point or another cycle?

The Panorama documentary is shocking, but it is not surprising. Survivors, campaigners, and many frontline officers themselves have long spoken about toxic cultures, cover-ups, and the cost of silence.

The question now is whether this will be a genuine turning point, or simply another chapter in a cycle of outrage and apology.

As one former senior officer told the BBC: “I’ve seen enough to say there is a highly toxic culture of hyper-sexualised male behaviour, misogyny, racism, and unlawful violence.”

Survivors and communities deserve a policing culture where those words no longer describe reality.

Policing by consent depends on trust. That trust has been broken - not just by the crimes of individuals but by a culture that enabled them.

The Panorama investigation has once again forced the country to confront an uncomfortable truth: until misogyny and racism are treated with the seriousness of corruption, until survivors’ voices are not just heard but acted upon, trust will remain out of reach.

Change is possible. We have seen glimpses of it in individual officers, in pockets of reform, in survivor-led initiatives. But change cannot remain patchy, fragile, or cosmetic. It must be systemic, urgent, and survivor-centred.

Because behind every toxic joke, every shrug of disbelief, every act of violence excused, there are lives put at risk, survivors left unheard, and communities stripped of faith in those sworn to protect them.

That is the cost. And it is a cost we cannot continue to pay.